Writing for Posterity

Primus inter pares

In the following scene from the Epic of Gilgamesh (c. 2600 BCE), Gilgamesh and his sidekick Enkidu have just sweet-talked the mountain ogre Huwawa into revealing his cave:

Gilgamesh found his way to Huwawa’s side. He crept up to him slowly, as one would with a snake. He moved in to kiss him, but then punched his face with a clenched fist. Huwawa bared his teeth at him. Gilgamesh and Enkidu pulled him from his house and threw a halter over him as over a wild bull. They tied his arms and bound his elbows like a captive man.

Huwawa begged for mercy, Gilgamesh was moved, but Enkidu reminded him of the monster’s nature and forced his hand. They cut off Huwawa’s head, stuffed it in a leather sack, then went home.

Skip forward 1800 years to Homer’s Odyssey (c. 800 BCE). Odysseus and his men are trapped in the cave of a Cyclops who has just eaten several of their number:

“Hey, Cyclops,” I said, “you’ve eaten a load of manflesh, so take this bowl and drink some wine, then you’ll see what kind of liquor we had on my ship. I was bringing it to you as an offering, in the hope that you’d take pity upon me and help me get home, but all you did was behave in this disgraceful way. You ought to be ashamed of yourself — how can you expect people to come visit you if you treat them this way?”

He took the bowl and drank. He was so delighted with the taste of the wine that he asked me for another. “Please,” he said, “give me some more, and tell me your name. I want to make you a guest-present. We have wine here, our soil grows grapes and the sun ripens them, but this drinks like nectar and ambrosia in one.”

I gave him some more, three bowls in all, which he drank down without a second thought. When I saw that the wine had gotten to his head, I said to him as credibly as I could: “Cyclops, you ask my name and I’ll tell it you, then give me the present you promised. My name is Nobody, which is what my father and mother and my friends have always called me.”

“Then I’ll eat all Nobody’s comrades before Nobody, saving Nobody for last. This is the present that I will make him.”

As he spoke he tottered, then fell face up on the ground, his head lolling to one side as he drunkenly vomited up wine and chunks of meat.

Which, as we all know, was how they had time to prepare a firebrand with which to destroy his eye, and why when his cries brought the other cyclopes, he told them “Nobody is killing me!”

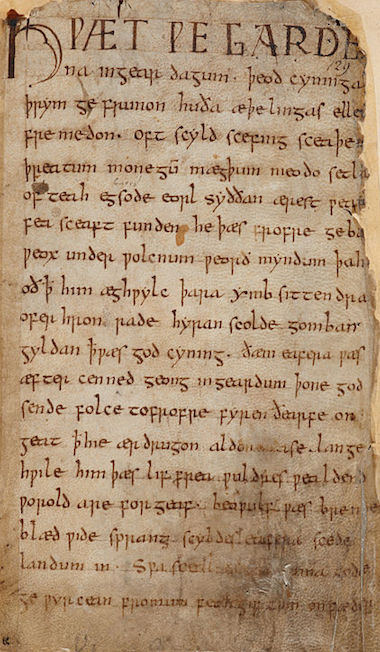

Leap ahead another 1800 years to Beowulf (c. 1000 CE):

My plan was to pounce, pin him down in a tight grip and grapple him to death — have him panting for life, powerless and clasped in my bare hands, his body in thrall. But I couldn’t stop him from slipping my hold. The Lord allowed it, my lock on him wasn’t strong enough, he struggled fiercely and broke and ran. Yet he bought his freedom at a high price, for he left his hand and arm and shoulder to show he had been here, a cold comfort for having come among us. And now he won’t be long for this world.

These three excerpts span nearly five millennia, yet the last tale would be as familiar to the authors of the first as the first would be to the authors of the last. The cultures of Mesopotamia, Homeric Greece and the Anglo-Saxon Dark Ages were far from identical, but — because they shared a similar level of technology, and a commensurately mythopoetic understanding of nature — their stories are mutually comprehensible, serving as a reflection of how human beings lived and believed for most of history.

Accelerando

After the Renaissance, man’s relationship to nature changed. In the 16th century, François Rabelais wrote about Gargantua and Pantagruel without any expectation that those characters would be taken as real creatures — giants were no longer possible in a work of verisimilitude. A generation later Cervantes turned giants into an example of the fantastic and unbelievable, painting as comedically quaint something that had long felt true to most of mankind.

Over the course of the 17th and 18th centuries, true-seeming stories became less and less like Gilgamesh and Beowulf, and did so at the same ever-increasing pace at which technology and culture changed during those centuries.

Imaginative narrative slowly refocused from artistic representations of the past to speculative representations of the future. By the late 19th century, authors like Jules Verne and H.G. Wells seemed to realize that they were living in a world farther from that of Cervantes than his had been from that of Gilgamesh, and that the rate of change was still increasing. Critics have long maintained that science fiction was, as a genre, a reaction to man’s discomfort with the machine age, citing Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein as a cautionary tale in that vein. I think it arose because the future became, for the first time in history, more interesting than the past.

Modernity

To a modern reader, the notion of men armed with swords facing an ogre, cyclops or troll conjures images of Ray Harryhausen special effects, fantasy novels and teenage boys playing Dungeons and Dragons. It’s just not the stuff of real life. Likewise, it’s difficult to see stories in which characters spend two months at sea to cross the Atlantic or dispatch a rider with a handwritten letter as anything but antique curios and literary museum pieces.

We live in a world of jet airplanes, machine guns, cluster bombs, cellular telephones, email and the World Wide Web. In order to write stories that feel true, we must write our characters — who are not themselves any different from the human beings depicted in the Epic of Gilgamesh — into a world that resembles our own, just as every generation has done before us.

Unfortunately, the half-life of fiction continues to shorten at the same geometric rate at which our technology advances. It took over five thousand years to move beyond the world of Gilgamesh, but we already take for granted ways of living, working and communicating that were impossible twenty-five years ago. For example, if I were to write something like:

John waited up for Susan. He watched the news, Letterman, eagles flying over billowing flags, then sat -- ghostlit by cold blue static -- still waiting.

It might resonate with those old enough to remember a time before cable television, back when there were three or four channels, all of which signed off by two o’clock in the morning, but it’s unlikely to make anyone born in North America after 1985 feel anything at all.

The gallery of the nearly obsolete includes — as of this writing — telephone dial tones and FM radio static, and will soon include folding a newspaper, and shortly thereafter, given the prevalence of GPS-enabled mobile phones, folding a map. Things that are relatively recent additions to the human condition, like SMS, will be found solely in costume period dramas within the lifetime of anyone likely to read this.

I’m still trying to figure out a way forward. Do we retreat into high allegory, like Italo Calvino? Write Medieval detective novels in the manner of Umberto Eco? Whatever it is, we can do it — we can imagine it for you wholesale.

NOTES

Gilgamesh translation by the author. Likewise the Odyssey translation, though with a few phrases lifted from Samuel Butler. Beowulf translation by Seamus Heaney.

⁂

This entry is part of my journal, published April 28, 2008, in New York.