Sing, O Muse

The Odyssey famously begins with an exhortation, here translated by Robert Fagles:

Sing to me of the man, Muse, the man of twists and turns driven time and again off course, once he had plundered the hallowed heights of Troy.

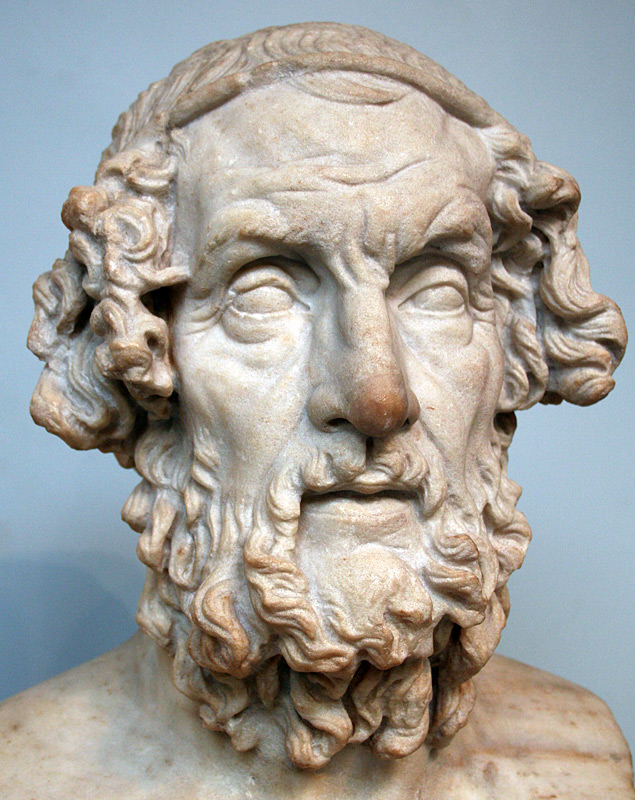

And sing Homer almost certainly did. The epic tradition was one of song, in which the poet would re-work the framework of each story with every telling, building up the lyric out of formulaic rhyming phrases to keep the meter while accompanying himself with a lyre. It is these rhyming phrases that give us the classic Homeric epithets (“swift-footed Achilles”, and so on).

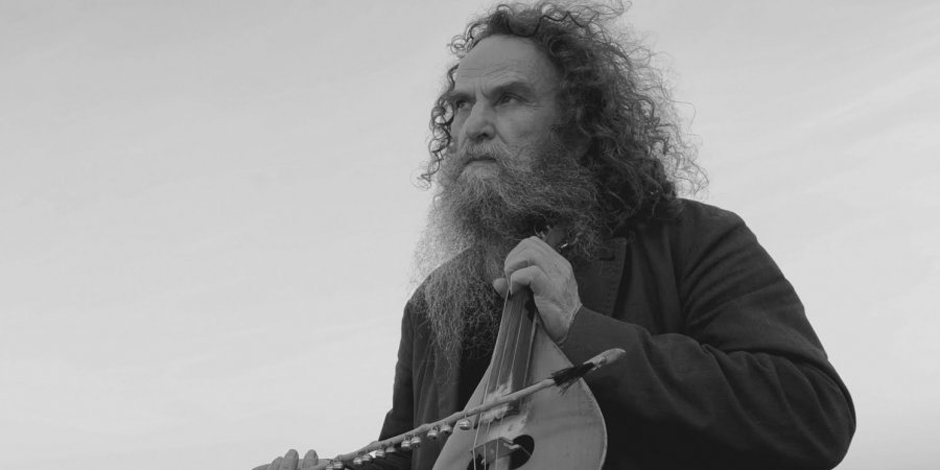

Ψαραντώνης

Some years ago, a pair of fresh-made friends in Athens – one of them from Crete – took me to a Cretan restaurant for dinner. When we arrived, we were told that there would be a cover charge and we’d only be able to order from a reduced menu because there was a special performer that night. They inquired as to the identity of the performer, and both went pale when they heard his name.

The man we saw that night is Psarantonis, a cultural treasure and folk hero to Greeks, particularly Cretans. He is renowned for his lyrics, his voice, and most of all his ability with the lyra – a long lost descendant of the lyre Homer would have used.

Although he fills large halls and plays major festivals, that night he was performing to around twenty five of us with members of his family backing him on a lute and a sort of Greek bodhrán.

I had no idea what to expect, but it turned out to be one of the most powerful concerts I’ve ever attended. His music rises from deep antiquity, his voice the growl of the Demiurge.

Between sets Psarantonis came to our table to drink shots of clear hot fire with us, and from that day forth the sight of him – eyes shut and singing his muse while playing that ancient instrument – has been my image of blind Homer entertaining kings in the Bronze Age.

Ὀδυσσεύς

A lifelong fascination with the Homeric epics combined with an interest in folk music may have over-prepared me to enjoy O Brother, Where Art Thou?, itself a modern adaptation of The Odyssey.

In particular, the reoccurring theme song Man of Constant Sorrow is more deeply appropriate than one might realize. One of the most common epithets used for Odysseus is πολύτλας (“polutas”), which is usually translated as “long-suffering”. He is, in the original, a man of constant sorrow who sees trouble all his days, bids farewell to the place where he was born and raised and is, indeed, bound to ramble.

I initially suspected that the song had been re-written or the lyrics doctored to be appropriate to Homer, but no. The song was first made popular in more or less the form presented in the film by the Stanley Brothers in 1951. However, the song is much older than that – hundreds of years so in the opinion of the surviving Stanley Brother – and we can trace the modern version back as far as 1913, when it was published under the title Farewell Song… by a blind fiddler called Richard Burnett.

Sing, O Muse.

⁂

This entry is part of my journal, published May 15, 2013, in New York.