Father Belloc was well acquainted with the goatish side of infinite God, for it was to him that the villagers brought their abandoned hopes and baffled desires, their most daring amorous adventures recounted in voices coarsely thrilling.

Sitting behind the wooden partition listening to their sins, his flesh crept up like a rosebud from the bush. He fingered it in his pocket, his body aching to do as the Lord must intend. Should he show it to Madame Lenoir? Most had shown more to strangers in the pale moonlight.

For him, of sensual pleasure only roots and graftings were to be had, and it was his war against the rose that ought to be crowned king that occupied him when Marc and Sylvie arrived on behalf of their mother to ask a thing too pitiful even to refuse.

– We’ve sat so long at the bedside of her pain.

It was a sin as grave as any, but he no longer believed as he once had. That night Belloc climbed the cold staircase to tell her how blest was the paradise to come, and together they wrote a letter of pardon to be presented in the hereafter.

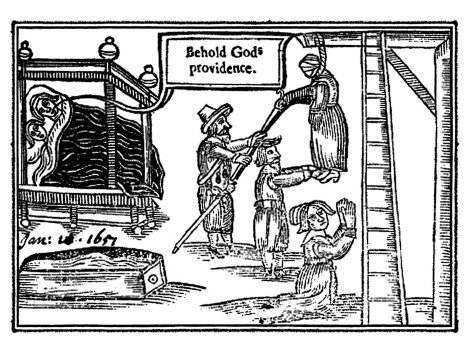

– Consecrate the rope, father.

The candle flame began to flutter and dogs barked to wake the moon. Her feet dangling, pawing at the air like the frail first steps of a faun. A phantom relief passed through Marc and Sylvie before the tears.

– With kindnesses we have murdered.

Belloc departed carrying the letter, the rope, and his broken faith. Later, peering out a window in the church’s basement he read all that was written in the colourless sky, sighed, then closed the furnace door. There would be nothing here to find if any came looking.

⁂

This entry is part of my journal, published January 7, 2013, in Airplane.